AI Summary

- Microsoft’s Aurora AI generates a 10-day global forecast in 57 seconds, a ~5,000x speedup over traditional models, while outperforming both the ECMWF and Google’s GraphCast on key metrics.

- Its foundation model architecture excels at forecasting extreme weather, air quality, and GHG concentrations, offering transformative operational advantages for industries like utilities and power generation.

- By running on commodity hardware, Aurora democratizes access to elite forecasting, though its “black box” nature highlights the need for hybrid systems that blend AI speed with physical interpretability.

I explored Aurora last week and watched it spit out a ten-day global weather forecast in fifty-seven seconds. On my local PC. While ECMWF’s operational model was still grinding through hour two of its usual four-hour computational slog.

That’s the kind of performance gap that makes you do a double-take at your monitor.

The Architecture That Actually Works

Aurora represents Microsoft’s shot at building a foundation model for Earth systems, and unlike most AI projects hunting for relevance, this one tackles a genuine computational nightmare.

Traditional weather prediction works like this: chop the atmosphere into millions of grid cells, solve physics equations at each point, repeat until your supercomputer overheats or the forecast completes—whichever comes first. Aurora learned atmospheric patterns directly from over a million hours of real geophysical data instead.

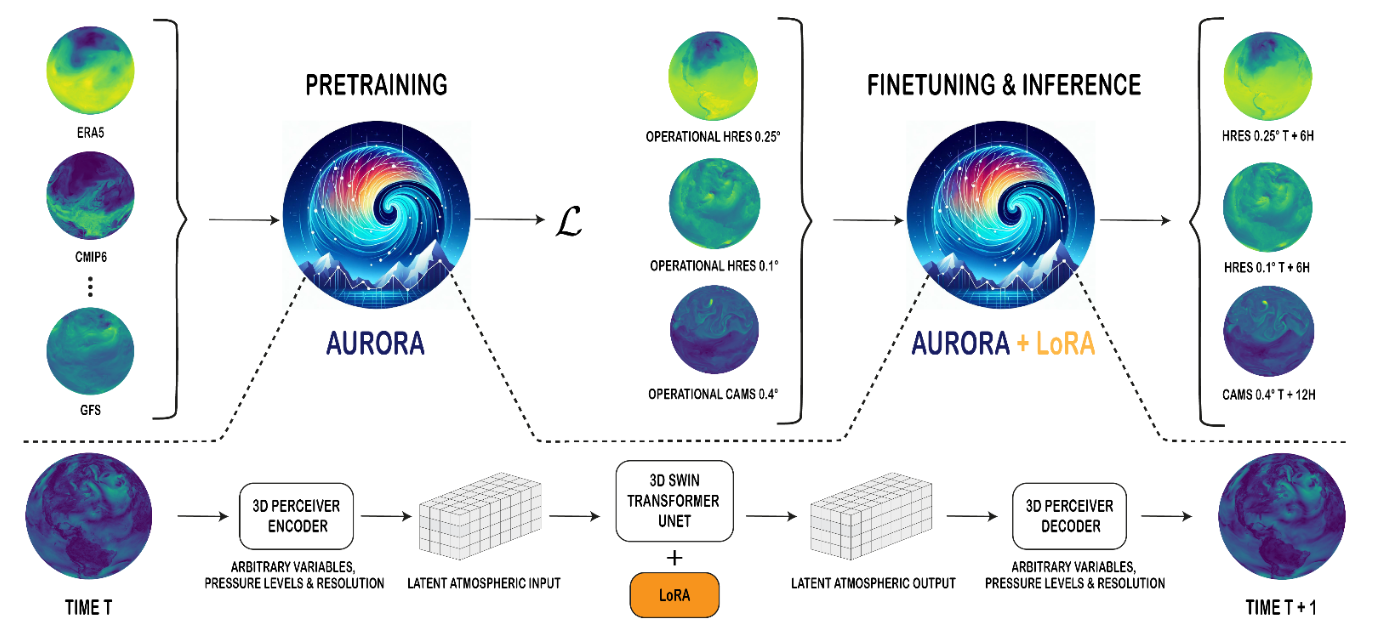

The 1.3 billion parameter model uses a flexible 3D Swin Transformer with Perceiver-based encoders and decoders that handle the multi-scale chaos making weather computationally expensive. Storm systems nest inside each other like Russian dolls—local thunderstorms emerge from continental temperature gradients, jet streams mess with precipitation patterns thousands of miles away. Traditional models struggle with these nested interactions. Aurora’s attention mechanisms track everything simultaneously, from molecular processes to planetary circulation.

Aurora is a 1.3 billion parameter foundation model for high-resolution forecasting of weather and atmospheric processes. Aurora is a flexible 3D Swin Transformer with 3D Perceiver-based encoders and decoders. At pretraining time, Aurora is optimized to minimize a loss on multiple heterogeneous datasets with different resolutions, variables, and pressure levels. The model is then fine-tuned in two stages: (1) short-lead time fine-tuning of the pretrained weights and (2) long-lead time (rollout) fine-tuning using Low Rank Adaptation (LoRA). The fine-tuned models are then deployed to tackle a diverse collection of operational forecasting scenarios at different resolutions.

Aurora is a 1.3 billion parameter foundation model for high-resolution forecasting of weather and atmospheric processes. Aurora is a flexible 3D Swin Transformer with 3D Perceiver-based encoders and decoders. At pretraining time, Aurora is optimized to minimize a loss on multiple heterogeneous datasets with different resolutions, variables, and pressure levels. The model is then fine-tuned in two stages: (1) short-lead time fine-tuning of the pretrained weights and (2) long-lead time (rollout) fine-tuning using Low Rank Adaptation (LoRA). The fine-tuned models are then deployed to tackle a diverse collection of operational forecasting scenarios at different resolutions.

The training approach deserves attention too. Aurora pretrains on heterogeneous datasets with different resolutions, variables, and pressure levels, then fine-tunes in two stages: short-lead time adjustments of pretrained weights, followed by long-lead time rollout fine-tuning using Low Rank Adaptation. This lets Aurora digest messy real-world data—satellite imagery, radar sweeps, surface observations—without the usual preprocessing gymnastics.

Performance That Actually Matters

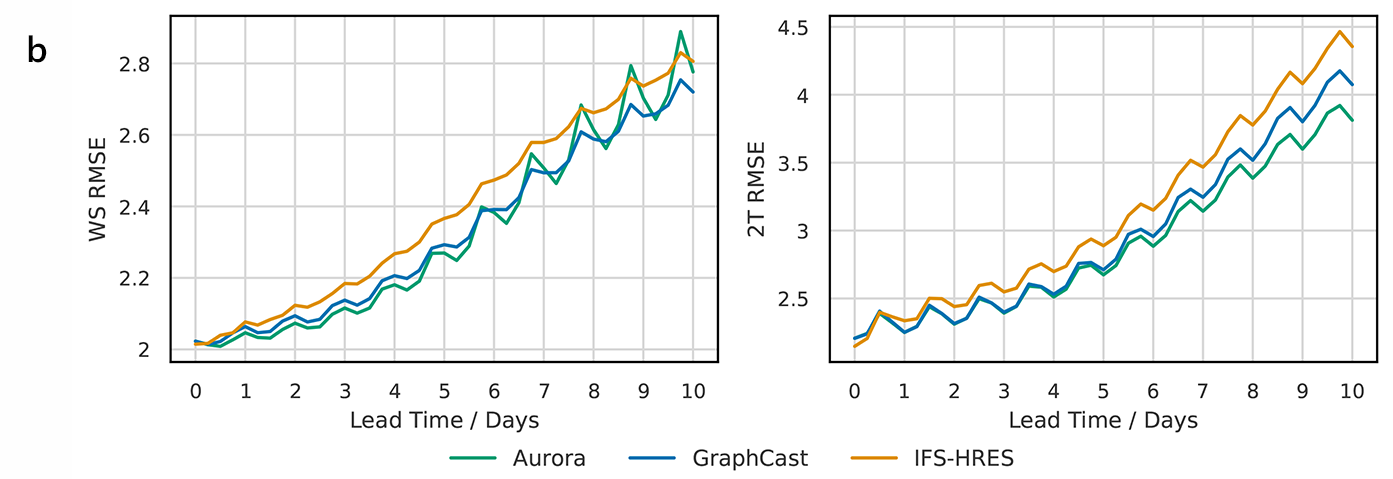

Aurora outperformed ECMWF’s high-resolution model on 90% of tested variables. When compared directly against GraphCast—Google’s previous state-of-the-art AI weather model—Aurora matched or exceeded performance on 94% of targets. The biggest gains showed up in the upper atmosphere, where GraphCast performance notoriously struggles, with improvements reaching 40%.

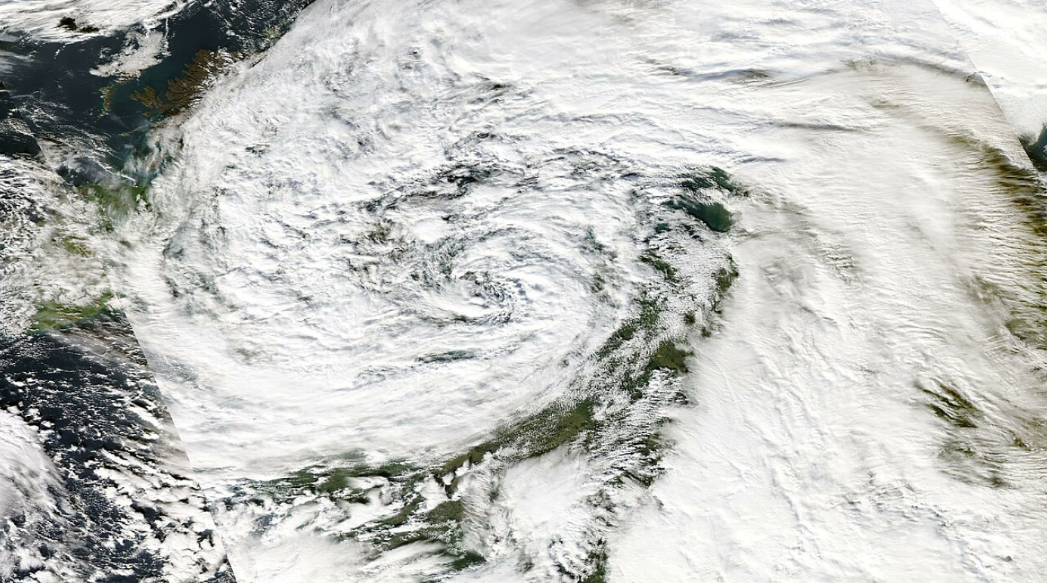

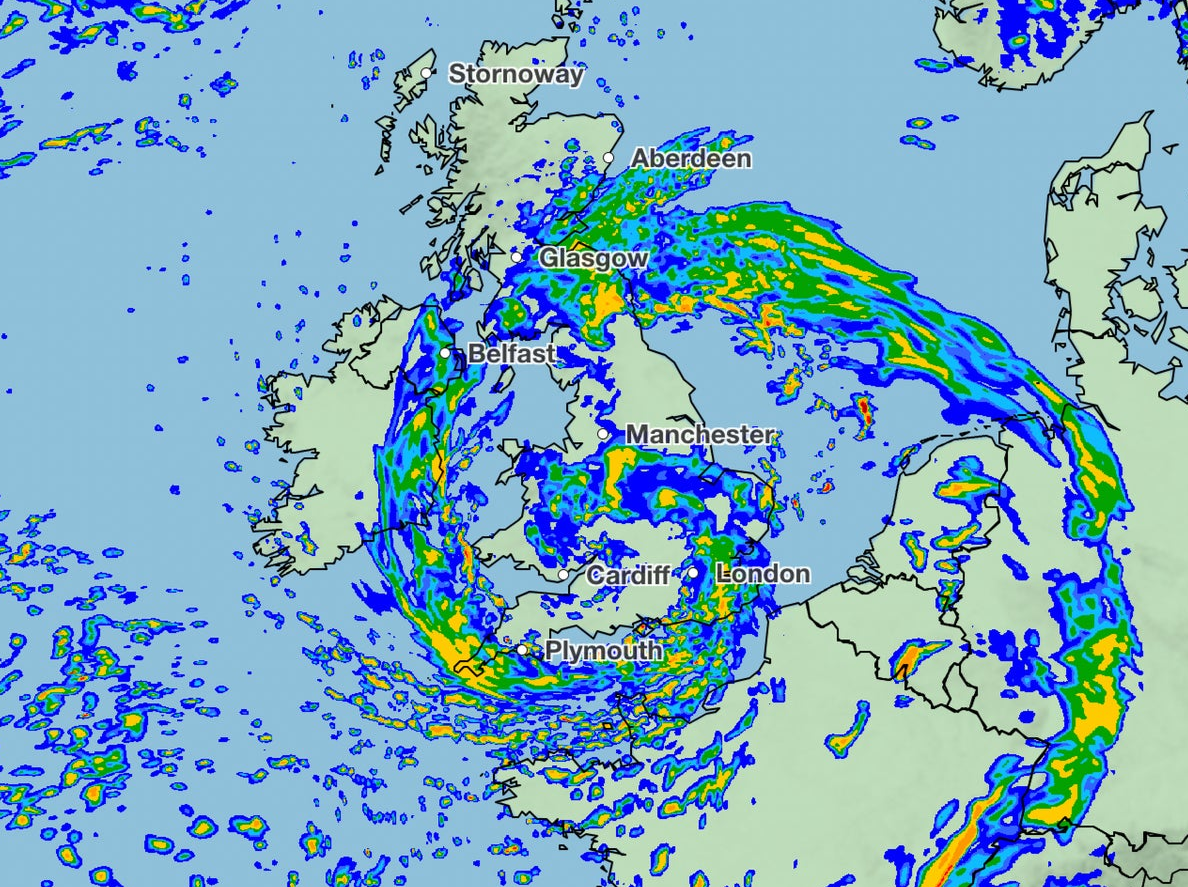

Storm Ciarán provided a real-world stress test. When this low-pressure system battered northwestern Europe in November 2023, it set new intensity records for England and caught existing weather models off guard. The rapid intensification and peak wind speeds exposed limitations in current prediction systems—exactly the kind of extreme event where Aurora’s pattern recognition capabilities could prove invaluable.

ECMWF of storm Ciarán over NW Europe

ECMWF of storm Ciarán over NW Europe

The speed differential feels almost unfair. Microsoft estimates Aurora delivers roughly 5,000x computational speedup over the Integrated Forecasting System. Traditional numerical weather prediction resembles computational archaeology—teams nursing finite difference equations through supercomputer clusters. Aurora runs inference on commodity hardware faster than most people stream Netflix.

Aurora vs. GraphCast: A Battle of Titans

Aurora beats out Google Deepmind’s GraphCast in various performance metrics.

Aurora beats out Google Deepmind’s GraphCast in various performance metrics.

The showdown between Microsoft’s Aurora and Google’s GraphCast isn’t about different jobs, but who can do the same job better. Both are deterministic models aiming for the single most accurate forecast possible. The rivalry pushes the boundaries of AI in meteorology.

While both models deliver state-of-the-art performance, their architectures differ. GraphCast uses a Graph Neural Network to process the world as a mesh of interconnected nodes. Aurora employs a 3D Swin Transformer, an approach that excels at capturing complex, multi-scale spatial relationships in three dimensions.

As performance benchmarks show, Aurora’s architecture currently gives it an edge, particularly in the upper atmosphere. This direct competition is rapidly accelerating progress, with each new model leapfrogging the last in a race for atmospheric prediction supremacy.

Beyond Weather: The Versatility Factor

Aurora’s foundation model architecture generalizes across environmental prediction tasks beautifully. The model can forecast atmospheric variables from temperature and wind speed to air pollution levels and greenhouse gas concentrations.

Air quality forecasting provides a compelling example. Aurora produces accurate five-day global air pollution forecasts at 0.4° spatial resolution, outperforming the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service on 74% of targets. Predicting atmospheric gases like nitrogen dioxide is notoriously difficult due to their spatially heterogeneous nature and complex diurnal cycles—sunlight reduces background levels through photolysis, while densely populated areas show emission spikes. Aurora captures both the extremes and background levels accurately.

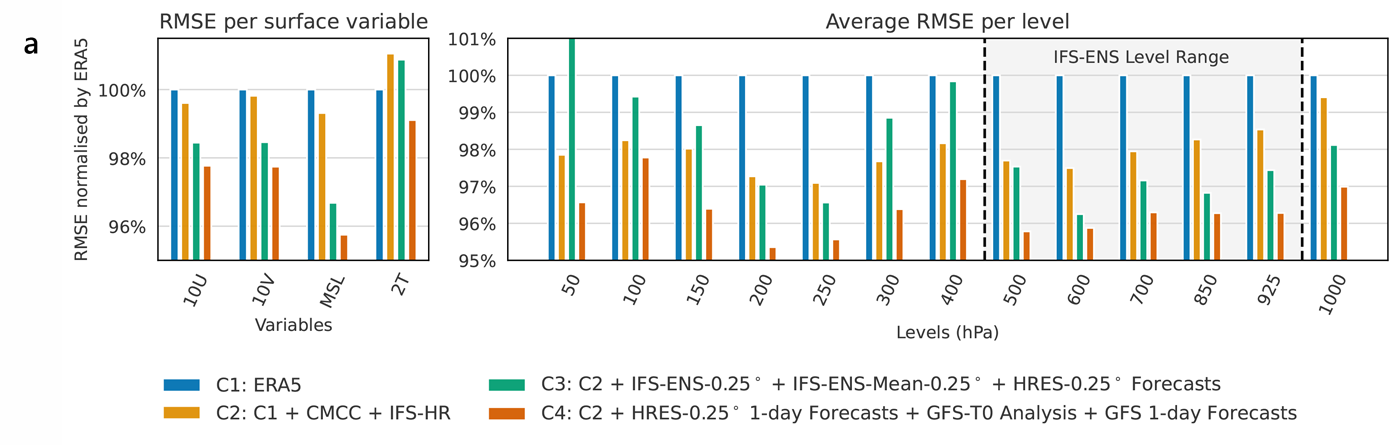

Impressive performance vs ERA5 reanalysis data for ERA5 at 6h lead

Impressive performance vs ERA5 reanalysis data for ERA5 at 6h lead

This versatility distinguishes Aurora from traditional numerical models, which typically specialize in narrow domains. The same architecture predicting hurricane tracks can forecast agricultural growing seasons or urban heat effects. It’s like having a meteorological Swiss Army knife.

The Access Revolution

Aurora’s computational efficiency has serious implications for global weather prediction access. Small nations and regional authorities can now access forecast quality previously reserved for meteorological superpowers. The barrier drops from supercomputer-class infrastructure to workstation-class hardware.

Bangladesh doesn’t need ECMWF-equivalent infrastructure for ECMWF-quality cyclone predictions anymore. They need a decent GPU and reliable internet. This could prove transformative for disaster preparedness in regions where accurate forecasting saves lives.

The foundation model approach particularly benefits data-sparse regions. Aurora’s diverse pretraining corpus enables it to excel even with limited fine-tuning data for specific tasks—exactly what developing nations and polar regions need for localized forecasting capabilities. You can learn more about its open-source availability here.

The Interpretability Problem

Aurora suffers from standard deep learning opacity. When it predicts rapid hurricane intensification, the reasoning disappears into transformer attention weights and embedding spaces. Traditional models at least show their work through differential equations and thermodynamic principles.

This matters in operational meteorology. Emergency management officials need confidence intervals and failure modes, not just point predictions. “The AI recommends evacuation” doesn’t inspire the same institutional trust as “pressure gradients indicate rapid intensification based on established physics.”

Hybrid approaches probably make the most sense—combine Aurora’s computational efficiency with traditional models’ physical interpretability. Let AI handle pattern recognition and rapid inference while physics-based models provide sanity checks and explainable backups.

Why I Actually Care About This

Six years of weather-dependent work has turned me into an accidental meteorologist. I understand more about ensemble spreads, convective parameterization, and model bias correction than I ever wanted to. When you’re responsible for decisions that hinge on whether the GFS or NAM handles lake-effect snow better, you develop opinions about atmospheric modeling fast.

Aurora represents something fundamentally different. For industries like utilities and power generation that live or die by weather accuracy, Aurora’s combination of speed and precision could reshape how they consume meteorological data entirely.

Think about utility load forecasting. Right now, operators blend multiple weather models with complex bias corrections, waiting hours for updated forecasts while demand patterns shift in real-time. Aurora could deliver superior predictions in under a minute, enabling reactive load management that currently isn’t computationally feasible.

Power generation scheduling faces similar constraints. Wind and solar forecasting relies on numerical weather models that update every six hours with multi-hour computational delays. Aurora’s rapid refresh capability could enable minute-by-minute generation adjustments based on atmospheric conditions that traditional models miss entirely.

The air quality forecasting capabilities add another dimension. Industrial facilities could adjust operations in real-time based on atmospheric dispersion predictions, optimizing both environmental compliance and operational efficiency in ways that current systems can’t support.

This feels like a genuine step change rather than incremental improvement. Industries that have spent decades working around weather model limitations suddenly have access to forecasting capabilities that eliminate many of those constraints. That’s the kind of technological shift that transforms entire operational approaches.

What’s Coming Next

Aurora represents meteorology’s first serious encounter with foundation model capabilities. The performance gaps are too substantial to ignore, efficiency improvements too dramatic to dismiss. This will accelerate AI adoption across atmospheric sciences faster than incremental progress ever could.

The research demonstrates clear scaling benefits—bigger models achieve lower validation losses, with roughly 5% improvement for every doubling of model size. Combined with the proven advantages of diverse pretraining data, this suggests Aurora represents just the beginning of what foundation models can achieve in Earth system modeling.

Expect next-generation operational forecasting systems to embrace aggressive hybridization. Physics-informed neural networks embedding thermodynamic constraints directly into loss functions. Ensemble methods blending AI predictions with traditional numerical approaches. Uncertainty quantification frameworks providing confidence bounds around deep learning forecasts.

The weather prediction revolution just moved from academic curiosity to operational necessity. Aurora proved foundation models can master atmospheric physics well enough to outperform decades of supercomputing refinement. The rest of meteorology will spend considerable time figuring out what that means for everything else.

Those sub-minute global forecasts still feel slightly surreal—a desktop computer peering ten days into atmospheric chaos with better accuracy than humanity’s most sophisticated weather machines. The future of meteorology arrived faster than most predicted, which feels appropriately ironic for the field.